You can get in touch with me by telephone or text during normal business hours, through the email form below, or by postal mail at the address listed below.

For emergencies, please call, do not use the contact form.

Contact

Contact Information

484-447-6945

P.O. Box 5011

Limerick, PA 19464

drjessvet.com

Gastric Ulceration in Horses

The Root of All Equine Evil?

Posted on: April 15, 2014

Stomach (gastric) ulcers in horses has been a hot topic for the last few years, and for good reason.

Recent research has indicated that many more horses are suffering from this condition than previously thought. Also, the finding that even backyard, non-performance horses have ulcers is surprising to most people, since the misconception in the past was that only high-stress horses such as racehorses and those showing often had problems with gastric ulcers. It is estimated that between 50 and 90% of horses have ulcers, depending on the class of horse, and even foals can suffer from them.

Recent research has indicated that many more horses are suffering from this condition than previously thought. Also, the finding that even backyard, non-performance horses have ulcers is surprising to most people, since the misconception in the past was that only high-stress horses such as racehorses and those showing often had problems with gastric ulcers. It is estimated that between 50 and 90% of horses have ulcers, depending on the class of horse, and even foals can suffer from them.

Gastric ulceration occurs when the lining of the stomach is damaged by the acid normally produced to help break down ingested roughage. Horses in the wild graze throughout the day, so the constant production of stomach acid is buffered by a consis tent intake of fiber and saliva produced from chewing. Domesticated horses are often fed only twice a day, so although that acid continues to be produced 24 hours a day, there are several hours where no food is present in the stomach to digest, and therefore the acid is not buffered and is more likely to slosh around and cause damage. Feeding of grain also contributes to gastric ulceration, as it increases the production of volatile fatty acids and this further upsets the normal pH of the stomach environment. The administration of some non-steroidal anti- inflammatories such as phenylbutazone and Banamine, when used in high concentrations or over a long period of time, can also promote ulcer formation by decreasing the protective mucous layer produced in the stomach.

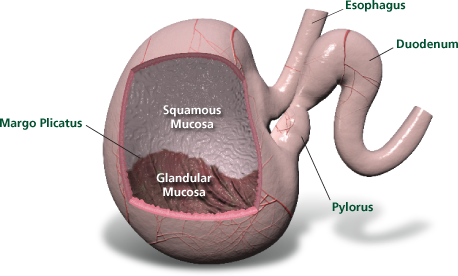

The horse's stomach is split into two parts, the squamous, non-glandular upper portion, and the lower glandular portion. Acid is produced in the lower part, but so are buffering mucous and bicarbonate, so the lower part of the stomach is not usually affected by ulcers in adult horses. Acid splashing into the upper, unprotected, non-glandular part of the stomach leads to most ulcers.

The horse's stomach is split into two parts, the squamous, non-glandular upper portion, and the lower glandular portion. Acid is produced in the lower part, but so are buffering mucous and bicarbonate, so the lower part of the stomach is not usually affected by ulcers in adult horses. Acid splashing into the upper, unprotected, non-glandular part of the stomach leads to most ulcers.

There is a wide variety of signs associated with gastric ulcers in horses, and none of them are very specific to ulcers alone. The majority of affected horses never show any outward signs to alert us to the problem. Many horses with ulcer problems show changes in attitude or unwillingness to work. Other horses may be reluctant to eat or finish their grain, or colic repeatedly. Weight loss, poor quality haircoat, girthiness, grinding of the teeth and excessive salivation may also be seen.

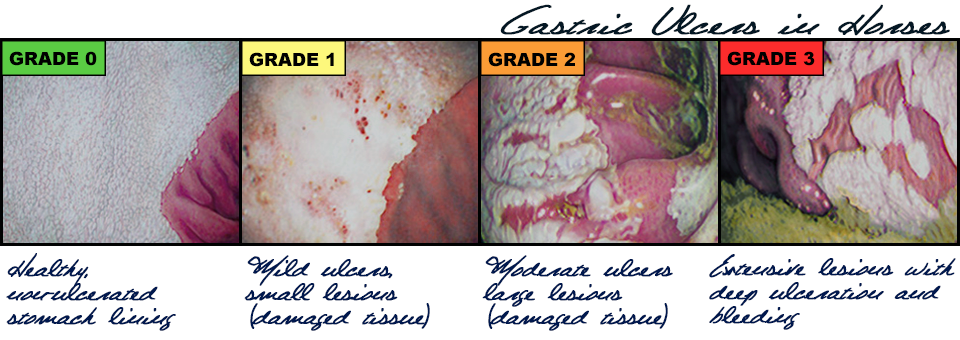

The only way to definitively diagnose gastric ulceration in horses is by gastroscopy, where a flexible three meter long endoscope is passed via one nostril down the esophagus and into the stomach. Often the upper portion of the small intestine can also be viewed. The procedure is simple and quick, with the most stressful part being withholding food and water before the exam! The duration of withholding varies between veterinarians. During the examination we are able to view both portions of the stomach and determine if ulceration is present, and then grade the lesions based on severity.

images of various stages of gastric ulcers in equine specimen (horse)

The treatment for gastric ulcerations in horses usually involves administering GastroGard, as paste form of the drug omeprazole, an acid pump inhibitor, which stops acid production. This is the only FDA approved product for treatment of gastric ulcers in horses. The treatment is usually once a day for one month, and then depending on the prescriber's instructions may taper over varying lengths of time. Depending on the horse's exam findings, response to treatment, and finances, we might also use drugs such as cimetidine or ranitidine, which partially block acid production but have to be given several times a day; or sucralfate, which acts as a type of bandage to protect the stomach while other drugs lower acid levels. Using antacids as we would in humans is not as effective, as the effects are very short-lived and the volume needed is extremely high. There are many over the counter medications being sold for “treatment” of equine gastric ulcers, but there is no reliable scientific evidence that any of them actually prevent or treat ulcers (the exception being UlcerGard). They may be helpful in keeping ulcers at bay after successful treatment with FDA approved medications, but this should be discussed with a veterinarian on a case by case basis.

The best way to try to prevent ulcers from starting or recurring is to change the way we manage horses. The main goal is to have forage passing through the stomach as often as possible, in small amounts, to simulate the normal diet found in wild horses and optimize stomach function. Decreasing grain feeding and spreading any grain fed throughout the day in smaller portions also helps. Increasing turnout and decreasing stress is important, as is maintaining as regular a routine as possible. Studies have also shown that feeding alfalfa may help prevent ulcers by both encouraging saliva production and providing extra calcium to the diet, which acts as a natural antacid. UlcerGard is an over the counter omeprazole paste meant to be given once a day to prevent ulcers during times of stress, such as showing or transport, so this can also be helpful.

If you think your horse may have gastric ulcers, or has unexplained behavioral or recurrent colic issues, please contact your veterinarian to discuss if gastroscopy might be an option. The change seen in horses that have been successfully treated is often amazing, and can lead to a marked improvement in performance and overall horse happiness.