You can get in touch with me by telephone or text during normal business hours, through the email form below, or by postal mail at the address listed below.

For emergencies, please call, do not use the contact form.

Contact

Contact Information

484-447-6945

P.O. Box 5011

Limerick, PA 19464

drjessvet.com

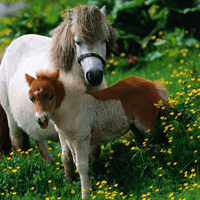

Vaccinations and Your Horse: I

What you need to know to protect your equine companions.

Posted on: March 10, 2015

Spring is coming

Along with the excitement of shedding horses (finally!) it is time to start thinking about vaccinations for our equine friends. There are many different vaccines available for several diseases, and this can be confusing to horse owners. When considering what vaccines to administer, we need to evaluate each horse as an individual, as their requirements will differ depending on their age, geographical location and potential exposure to diseases. The best person to assist in this decision making process is your veterinarian, as he or she can formulate a plan based on your horse's personal needs.

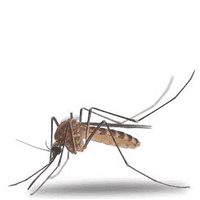

In this area (Mid-Atlantic), I prefer to administer yearly vaccinations in two “bunches”, one in the spring and one in the fall. In this way, we can provide optimum protection as close to the possible threat of disease as possible, and keep the immune system on its toes without over- stimulating it. Any vaccinations for mosquito or other insect-borne diseases (West Nile Virus, Potomac Horse Fever, Eastern and Western Encephalomyelitis) should be given in the spring. Vaccination for botulism is best done in the fall, as the disease is more common in the wet months of the year. Rabies vaccination can be done any time of year, as can strangles and rhino/flu. There are no established protective titer ranges for horse diseases at this time, so although we are able to draw blood and provide a number, we are unable to determine exactly what that means for protection of the horse's health.

If you are planning to begin administering a vaccine for a disease you have not previously vaccinated for, either in a mature horse or a foal, the horse will need to complete what is called a “primary course” of vaccination, in order to get the immune system primed to recognize the diseases as they are presented to the body. This course is generally two administrations, usually a month apart. The exceptions are botulism, which requires a course of three shots to be protective, and rabies, which we usually booster a year after the initial dose. Some West Nile Virus vaccines are also a one-dose primary course, but this varies by the drug company and product. Vaccines for diseases in pregnant mares such as rotavirus and the abortion-causing strain of EHV require 3 shots a month apart at a specific time during gestation. Pregnant mares also require their routine vaccines to be boostered one month prior to foaling to ensure the foal receives adequate antibodies in the colostrum (first milk). You should consult with your veterinarian regarding the proper timing of vaccination in pregnant mares and foals on an individual basis.

So what diseases should we be concerned about? Many clients are surprised to learn that their unvaccinated horse is at risk for many preventable diseases even though it may never leave the farm. Although vaccines are not fool-proof for preventing diseases, they definitely reduce the chance of contracting diseases and lessen the symptoms in affected individuals. Let's go through the most common equine diseases covered by vaccines one at a time:

Rabies

Rabies is a viral disease spread by the body fluids of an infected individual either into mucous membranes such as in the eyes or mouth, or through open wounds or bites. It is obviously also a zoonotic disease, meaning that it can be transmitted to humans by other animals. While there is no legal requirement for rabies vaccination in horses since they are not considered “pets”, and it is not especially common in horses, it is not a vaccine I would skip, as it is fatal. Any horse that lives outside is at risk of contracting rabies, even if stall-bound. The most common vectors of rabies to horses are skunks, raccoons, foxes and bats. The disease causes varying degrees of neurologic signs including inappetance, erratic behavior, drooling, and depression. Exposed animals are subject to quarantine, more so if unvaccinated. Not all exposed animals will die, but non-vaccinated symptomatic animals should be euthanized to reduce exposure to other animals and humans. The only definitive diagnostic test is one that requires euthanizing the horse and submitting the brain for evaluation. Rabies vaccine should be administered yearly and is a core vaccine recommended in all horses by the AAEP (American Association of Equine Practitioners).

Tetanus

Horses are exquisitely sensitive to infection with tetanus, which is caused by a clostridial bacteria found in soil and manure. Tetanus is another core vaccine recommended by the AAEP for all horses. Horses are usually infected with tetanus via a wound such as a laceration or a foot abscess, or also via the umbilicus of new foals. The disease is not contagious between individuals. Tetanus causes neurologic signs including alterations to the facial nerves that result in difficulty chewing or opening the mouth, improper function of the eyes, excessive reactivity to light or sound and a stilted gait. Tetanus is fatal in most horses although early cases may be treatable with tetanus antitoxin administration. Most horses should be vaccinated for tetanus once a year, and the vaccine is usually combined with other disease vaccines such as eastern and western encephalomyelitis. Horses with acute wounds should have a tetanus booster if they have not had one in the last six months.

Eastern and Western Equine Encephalomyelitis

These viral diseases are spread by bites from infected mosquitoes, with wild birds and rodents acting as natural reservoirs for the disease. Therefore, any horse with access to the outdoors should be vaccinated against them. They are also zoonotic diseases, being spread to humans via infected mosquito bites, although horse to horse and horse to human transmission via mosquito bite is rare. These diseases cause neurologic signs such as difficulty swallowing, behavioral changes, impaired vision, seizures, circling and recumbency. EEE and WEE have the potential to be lethal, although many cases are able to recover with supportive care. The vaccine for EEE and WEE is usually combined with a tetanus vaccine. In this area, most horses are vaccinated once a year, although horses living in or travelling to warmer areas such as Florida should be boostered appropriate to their situation. The AAEP recognizes both EEE and WEE as core vaccines for every horse.

West Nile Virus

Another AAEP core vaccine, West Nile is a virus spread by infected mosquitoes via birds and is another potentially zoonotic disease. Again, any horses with outdoor access should be vaccinated. The virus cannot be spread directly from horse to horse or horse to human. Indirect transmission between horses and humans via mosquitoes is unlikely as horses do not retain a large amount of virus in their bloodstream after infection. This virus causes similar neurologic signs to EEE and WEE as it leads to encephalomyelitis. Although horses usually recover (although many have lasting deficits) with supportive treatment, approximately 33% of infected horses succumb to the disease. The booster recommendations for WNV are similar to those for EEE/WEE as far as mosquito-prone areas are concerned.

Rhinopneumonitis (Rhino/EHV) and Influenza (Flu)

Although not a core vaccine, rhino/flu (usually combined into one vaccine) virus coverage is important for horses that come in contact with other horses directly, or indirectly by sharing stalls, water buckets, etc. as these diseases are spread by contact with infective nasal secretions. Horses that live isolated from other horses (aerosolized particles from a cough can travel over 30 feet!) with caretakers that do not contact other horses off the farm are at low risk of contracting these viruses and therefore may not require the vaccination. This vaccine can be given either once a year or twice a year depending on exposure. These two viruses cause respiratory disease in most cases, but variants of EHV can cause neurologic disease or abortion in pregnant mares (Pneumabort is one vaccine used to protect from abortive EHV). Young horses are more susceptible to both viruses. Currently available EHV vaccines have a very low efficacy against the neurologic form of EHV, unfortunately.

Botulism

Botulism is a bacterial disease caused by ingestion of, or wound contamination by, infective spores of a clostridial bacteria found normally in soil. Check out my earlier post on botulism for more detailed info on the disease. Botulism vaccine is not given in all parts of the country, but it is especially important in this area and other places where wet weather and mud are commonplace. It is not considered a core vaccine by AAEP, but having seen several cases in this area, it is one vaccine I would not skip. This vaccine is usually administered once a year and I prefer to give it in the fall since there are more botulism cases during muddy weather.

Stay tuned for part two

I will continue discussing more risk-based equine vaccinations, including Potomac Horse Fever, Strangles, Rotavirus, and Pneumabort. Enjoy this beautiful weather in the meantime!